When you’re cycling uphill, you don’t usually want to stop. You lose momentum, and it’s hard to get started again. But sometimes you notice something that makes the effort worthwhile. As I pedalled from Hazel Road shore, uphill past the boarded up Yacht Tavern, towards the railway bridge on Sea Road, this stunning double dandelion caught my eye. Initially, I cycled past, but the lure was too strong. I went back, stopped to really take it in, then struggled to start back up the hill.

As I write this, I’ve heard a Dunnock singing. A Dunnock, not ‘the’ Dunnock, because this week, for the first time, I heard two. One was perched on top of the crab apple, and as I paused to listen to him, I then heard another sing in response from further away. Until now, I’d assumed it was one bird moving around, but now I know different!

I think that when you choose to spend a little longer, you notice more, and you become more connected to the nature around you.

At the start of the week, I went to Hilliers Arboretum in search of early spring flowers, and wasn’t disappointed. As well as snowdrops and primroses, there were still a few witch hazel flowers (I love these!) and a hellebore was being visited by a bee.

The next day, I inadvertently disturbed an orange ladybird in a pot in the back garden.

There’s nothing surprising about the moss on our front garden wall; i know it’s there. The vibrant green can be relied on to put a smile on my face throughout winter. I pause to appreciate it every morning.

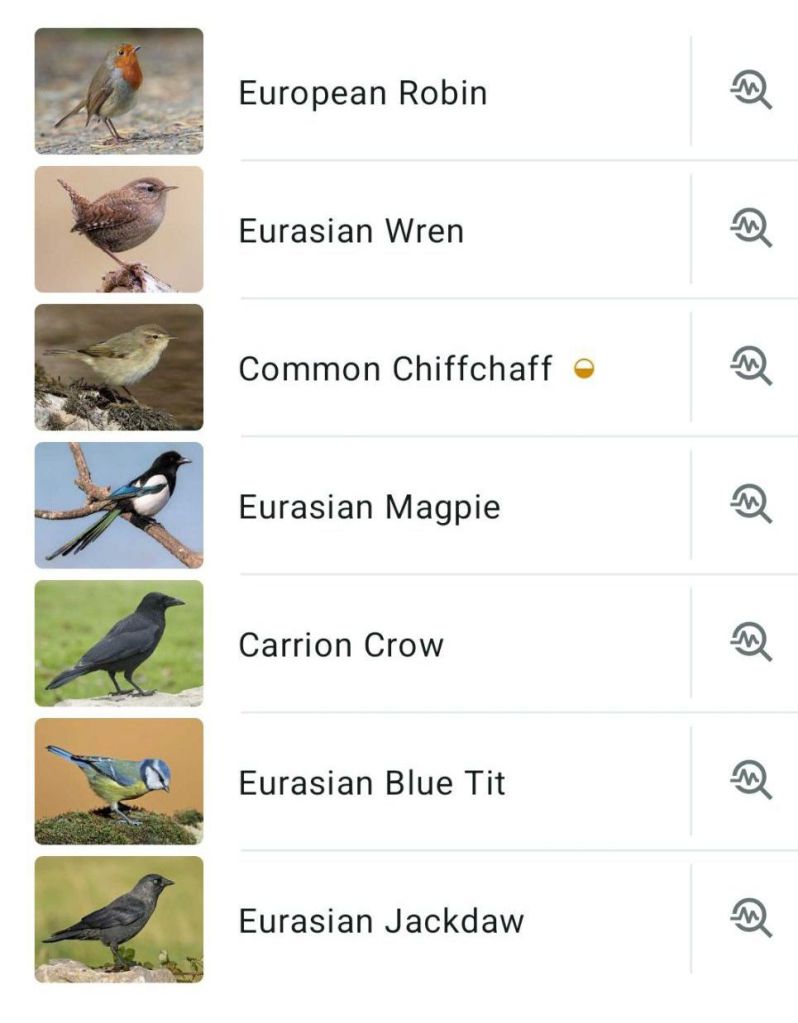

Over on Peartree Green nature reserve, the birdsong is starting to build as the season turns. One morning, I used the Merlin app to capture the moment. Seven species from one spot in the upper woodland.

As I walked back along the track, I stopped at the elm hedge on Sea Road to see what was around. Plum cherries are in flower, and I noticed several leathery fungus fruits on the adjacent shrub. I don’t know what they are, but it doesn’t matter. They’re fascinating.

The final joyful moment this week was this Great Spotted Woodpecker on Southampton Common. I heard it drumming – a sound tbat sends shivers down my spine – and was looking for it when the friend I was meeting arrived. His eyesight is better, so he soon saw it. His phone camera is better too – this video is his.

If you listen carefully, you can hear me talking to a man and his daughter, as I point out where the woodpecker is. It’s joyful to experience these moments of nature, but even better to be able to help others to experience them too. I’m looking forward to what next week will bring!